Haskell/Zippers

Theseus and the Zipper

The Labyrinth

"Theseus, we have to do something" said Homer, chief marketing officer of Ancient Geeks Inc.. Theseus put the Minotaur action figure™ back onto the shelf and nodded. "Today's children are no longer interested in the ancient myths, they prefer modern heroes like Spiderman or Sponge Bob." Heroes. Theseus knew well how much he had been a hero in the labyrinth back then on Crete[1]. But those "modern heroes" did not even try to appear realistic. What made them so successful? Anyway, if the pending sales problems could not be resolved, the shareholders would certainly arrange a passage over the Styx for Ancient Geeks Inc.

"Heureka! Theseus, I have an idea: we implement your story with the Minotaur as a computer game! What do you say?" Homer was right. There had been several books, epic (and chart breaking) songs, a mandatory movie trilogy and uncountable Theseus & the Minotaur™ gimmicks, but a computer game was missing. "Perfect, then. Now, Theseus, your task is to implement the game".

A true hero, Theseus chose Haskell as the language to implement the company's redeeming product in. Of course, exploring the labyrinth of the Minotaur was to become one of the game's highlights. He pondered: "We have a two-dimensional labyrinth whose corridors can point in many directions. Of course, we can abstract from the detailed lengths and angles: for the purpose of finding the way out, we only need to know how the path forks. To keep things easy, we model the labyrinth as a tree. This way, the two branches of a fork cannot join again when walking deeper and the player cannot go round in circles. But I think there is enough opportunity to get lost; and this way, if the player is patient enough, they can explore the entire labyrinth with the left-hand rule."

data Node a = DeadEnd a

| Passage a (Node a)

| Fork a (Node a) (Node a)

Theseus made the nodes of the labyrinth carry an extra parameter of type a. Later on, it may hold game relevant information like the coordinates of the spot a node designates, the ambience around it, a list of game items that lie on the floor, or a list of monsters wandering in that section of the labyrinth. We assume that two helper functions

get :: Node a -> a put :: a -> Node a -> Node a

retrieve and change the value of type a stored in the first argument of every constructor of Node a.

Template:Exercises

"Mh, how to represent the player's current position in the labyrinth? The player can explore deeper by choosing left or right branches, like in"

turnRight :: Node a -> Maybe (Node a) turnRight (Fork _ l r) = Just r turnRight _ = Nothing

"But replacing the current top of the labyrinth with the corresponding sub-labyrinth this way is not an option, because the player cannot go back then." He pondered. "Ah, we can apply Ariadne's trick with the thread for going back. We simply represent the player's position by the list of branches their thread takes, the labyrinth always remains the same."

data Branch = KeepStraightOn

| TurnLeft

| TurnRight

type Thread = [Branch]

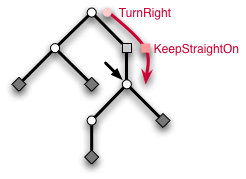

"For example, a thread [TurnRight,KeepStraightOn] means that the player took the right branch at the entrance and then went straight down a Passage to reach its current position. With the thread, the player can now explore the labyrinth by extending or shortening it. For instance, the function turnRight extends the thread by appending the TurnRight to it."

turnRight :: Thread -> Thread turnRight t = t ++ [TurnRight]

"To access the extra data, i.e. the game relevant items and such, we simply follow the thread into the labyrinth."

retrieve :: Thread -> Node a -> a retrieve [] n = get n retrieve (KeepStraightOn:bs) (Passage _ n) = retrieve bs n retrieve (TurnLeft :bs) (Fork _ l r) = retrieve bs l retrieve (TurnRight :bs) (Fork _ l r) = retrieve bs r

Theseus' satisfaction over this solution did not last long. "Unfortunately, if we want to extend the path or go back a step, we have to change the last element of the list. We could store the list in reverse, but even then, we have to follow the thread again and again to access the data in the labyrinth at the player's position. Both actions take time proportional to the length of the thread and for large labyrinths, this will be too long. Isn't there another way?"

Ariadne's Zipper

While Theseus was a skillful warrior, he did not train much in the art of programming and could not find a satisfying solution. After intense but fruitless cogitation, he decided to call his former love Ariadne to ask her for advice. After all, it was she who had the idea with the thread.

Template:Haskell speaker 2

Our hero immediately recognized the voice.

"Hello Ariadne, it's Theseus."

An uneasy silence paused the conversation. Theseus remembered well that he had abandoned her on the island of Naxos and knew that she would not appreciate his call. But Ancient Geeks Inc. was on the road to Hades and he had no choice.

"Uhm, darling, ... how are you?"

Ariadne retorted an icy response, Template:Haskell speaker 2

"Well, I uhm ... I need some help with a programming problem. I'm programming a new Theseus & the Minotaur™ computer game."

She jeered, Template:Haskell speaker 2

"Ariadne, please, I beg of you, Ancient Geeks Inc. is on the brink of insolvency. The game is our last hope!"

After a pause, she came to a decision.

Template:Haskell speaker 2

Theseus turned pale. But what could he do? The situation was desperate enough, so he agreed but only after negotiating Ariadne's share to a tenth.

After Theseus told Ariadne of the labyrinth representation he had in mind, she could immediately give advice,

Template:Haskell speaker 2

"Huh? What does the problem have to do with my fly?"

Template:Haskell speaker 2

"Ah."

Template:Haskell speaker 2

"I know for myself that I want fast updates, but how do I code it?"

Template:Haskell speaker 2

"But then, the problem is how to go back, because all those sub-labyrinths get lost that the player did not choose to branch into."

Template:Haskell speaker 2

Ariadne savored Theseus' puzzlement but quickly continued before he could complain that he already used Ariadne's thread,

Template:Haskell speaker 2

type Zipper a = (Thread a, Node a)

Theseus didn't say anything.

Template:Haskell speaker 2

data Branch a = KeepStraightOn a

| TurnLeft a (Node a)

| TurnRight a (Node a)

type Thread a = [Branch a]

Template:Haskell speaker 2

Theseus interrupts, "Wait, how would I implement this behavior as a function turnRight? And what about the first argument of type a for TurnRight? Ah, I see. We not only need to glue the branch that would get lost, but also the extra data of the Fork because it would otherwise get lost as well. So, we can generate a new branch by a preliminary"

branchRight (Fork x l r) = TurnRight x l

"Now, we have to somehow extend the existing thread with it."

Template:Haskell speaker 2

"Aha, this makes extending and going back take only constant time, not time proportional to the length as in my previous version. So the final version of turnRight is"

turnRight :: Zipper a -> Maybe (Zipper a) turnRight (t, Fork x l r) = Just (TurnRight x l : t, r) turnRight _ = Nothing

"That was not too difficult. So let's continue with keepStraightOn for going down a passage. This is even easier than choosing a branch as we only need to keep the extra data:"

keepStraightOn :: Zipper a -> Maybe (Zipper a) keepStraightOn (t, Passage x n) = Just (KeepStraightOn x : t, n) keepStraightOn _ = Nothing

Pleased, he continued, "But the interesting part is to go back, of course. Let's see..."

back :: Zipper a -> Maybe (Zipper a) back ([] , _) = Nothing back (KeepStraightOn x : t , n) = Just (t, Passage x n) back (TurnLeft x r : t , l) = Just (t, Fork x l r) back (TurnRight x l : t , r) = Just (t, Fork x l r)

"If the thread is empty, we're already at the entrance of the labyrinth and cannot go back. In all other cases, we have to wind up the thread. And thanks to the attachments to the thread, we can actually reconstruct the sub-labyrinth we came from."

Ariadne remarked, Template:Haskell speaker 2

Heureka! That was the solution Theseus sought and Ancient Geeks Inc. should prevail, even if partially sold to Ariadne Consulting. But one question remained:

"Why is it called zipper?"

Template:Haskell speaker 2

"'Ariadne's pearl necklace'," he articulated disdainfully. "As if your thread was any help back then on Crete."

Template:Haskell speaker 2 she replied.

"Bah, I need no thread," he defied the fact that he actually did need the thread to program the game.

Much to his surprise, she agreed, Template:Haskell speaker 2

"Ah." He didn't need Ariadne's thread but he needed Ariadne to tell him? That was too much.

"Thank you, Ariadne, good bye."

She did not hide her smirk as he could not see it anyway through the phone.

Half a year later, Theseus stopped in front of a shop window, defying the cold rain that tried to creep under his buttoned up anorak. Blinking letters announced

- find your way through the labyrinth of threads -

the great computer game by Ancient Geeks Inc.

He cursed the day when he called Ariadne and sold her a part of the company. Was it she who contrived the unfriendly takeover by WineOS Corp., led by Ariadne's husband Dionysus? Theseus watched the raindrops finding their way down the glass window. After the production line was changed, nobody would produce Theseus and the Minotaur™ merchandise anymore. He sighed. His time, the time of heroes, was over. Now came the super-heroes.

Differentiation of data types

The previous section has presented the zipper, a way to augment a tree-like data structure Node a with a finger that can focus on the different subtrees. While we constructed a zipper for a particular data structure Node a, the construction can be easily adapted to different tree data structures by hand.

Template:Exercises

Mechanical Differentiation

But there is also an entirely mechanical way to derive the zipper of any (suitably regular) data type. Surprisingly, 'derive' is to be taken literally, for the zipper can be obtained by the derivative of the data type, a discovery first described by Conor McBride[2]. The subsequent section is going to explicate this truly wonderful mathematical gem.

For a systematic construction, we need to calculate with types. The basics of structural calculations with types are outlined in a separate chapter [[../Generic Programming/]] and we will heavily rely on this material.

Let's look at some examples to see what their zippers have in common and how they hint differentiation. The type of binary tree is the fixed point of the recursive equation

When walking down the tree, we iteratively choose to enter the left or the right subtree and then glue the not-entered subtree to Ariadne's thread. Thus, the branches of our thread have the type

Similarly, the thread for a ternary tree

has branches of type

because at every step, we can choose between three subtrees and have to store the two subtrees we don't enter. Isn't this strikingly similar to the derivatives and ?

The key to the mystery is the notion of the one-hole context of a data structure. Imagine a data structure parameterised over a type , like the type of trees . If we were to remove one of the items of this type from the structure and somehow mark the now empty position, we obtain a structure with a marked hole. The result is called "one-hole context" and inserting an item of type into the hole gives back a completely filled . The hole acts as a distinguished position, a focus. The figures illustrate this.

|

|

Of course, we are interested in the type to give to a one-hole context, i.e. how to represent it in Haskell. The problem is how to efficiently mark the focus. But as we will see, finding a representation for one-hole contexts by induction on the structure of the type we want to take the one-hole context of automatically leads to an efficient data type[3]. So, given a data structure with a functor and an argument type , we want to calculate the type of one-hole contexts from the structure of . As our choice of notation already reveals, the rules for constructing one-hole contexts of sums, products and compositions are exactly Leibniz' rules for differentiation.

Of course, the function plug that fills a hole has the type .

So far, the syntax denotes the differentiation of functors, i.e. of a kind of type functions with one argument. But there is also a handy expression oriented notation slightly more suitable for calculation. The subscript indicates the variable with respect to which we want to differentiate. In general, we have

An example is

Of course, is just point-wise whereas is point-free style. Template:Exercises

Zippers via Differentiation

The above rules enable us to construct zippers for recursive data types where is a polynomial functor. A zipper is a focus on a particular subtree, i.e. substructure of type inside a large tree of the same type. As in the previous chapter, it can be represented by the subtree we want to focus at and the thread, that is the context in which the subtree resides

Now, the context is a series of steps each of which chooses a particular subtree among those in . Thus, the unchosen subtrees are collected together by the one-hole context . The hole of this context comes from removing the subtree we've chosen to enter. Putting things together, we have

or equivalently

To illustrate how a concrete calculation proceeds, let's systematically construct the zipper for our labyrinth data type

data Node a = DeadEnd a

| Passage a (Node a)

| Fork a (Node a) (Node a)

This recursive type is the fixed point

of the functor

In other words, we have

The derivative reads

and we get

Thus, the context reads

Comparing with

data Branch a = KeepStraightOn a

| TurnLeft a (Node a)

| TurnRight a (Node a)

type Thread a = [Branch a]

we see that both are exactly the same as expected! Template:Exercises

Differentiation of Fixed Point

There is more to data types than sums and products, we also have a fixed point operator with no direct correspondence in calculus. Consequently, the table is missing a rule of differentiation, namely how to differentiate fixed points :

As its formulation involves the chain rule in two variables, we delegate it to the exercises. Instead, we will calculate it for our concrete example type :

Of course, expanding further is of no use, but we can see this as a fixed point equation and arrive at

with the abbreviations

and

The recursive type is like a list with element types , only that the empty list is replaced by a base case of type . But given that the list is finite, we can replace the base case with and pull out of the list:

Comparing with the zipper we derived in the last paragraph, we see that the list type is our context

and that

In the end, we have

Thus, differentiating our concrete example with respect to yields the zipper up to an ! Template:Exercises

Differentation with respect to functions of the argument

When finding the type of a one-hole context one does d f(x)/d x. It is entirely possible to solve expressions like d f(x)/d g(x). For example, solving d x^4 / d x^2 gives 2x^2 , a two-hole context of a 4-tuple. The derivation is as follows let u=x^2 d x^4 / d x^2 = d u^2 /d u = 2u = 2 x^2 .

Zippers vs Contexts

In general however, zippers and one-hole contexts denote different things. The zipper is a focus on arbitrary subtrees whereas a one-hole context can only focus on the argument of a type constructor. Take for example the data type

data Tree a = Leaf a | Bin (Tree a) (Tree a)

which is the fixed point

The zipper can focus on subtrees whose top is Bin or Leaf but the hole of one-hole context of may only focus a Leafs because this is where the items of type reside. The derivative of only turned out to be the zipper because every top of a subtree is always decorated with an .

Template:Exercises

Conclusion

We close this section by asking how it may happen that rules from calculus appear in a discrete setting. Currently, nobody knows. But at least, there is a discrete notion of linear, namely in the sense of "exactly once". The key feature of the function that plugs an item of type into the hole of a one-hole context is the fact that the item is used exactly once, i.e. linearly. We may think of the plugging map as having type

where denotes a linear function, one that does not duplicate or ignore its argument, as in linear logic. In a sense, the one-hole context is a representation of the function space , which can be thought of being a linear approximation to .