Pascal Programming/Files

Ever wondered how to process bulks of data? Files are the solution in Pascal. You were already acquainted with some basics in the [[../Input and Output#Files|input and output]] chapter. Here we will elaborate more details as far as the Template:Abbr standard 7185 “Pascal” defines them. The “Extended Pascal” Template:Abbr standard 10206 defines even more features, but these will be covered in the second part of [[../|this WikiBook]].

File data types

So far we have been only handling text files, Template:Abbr files possessing the data type text, but there are more file types.

Concept

Mathematically speaking, a file is a bounded finite sequence. That means,

- components are oriented along an axis (sequence),

- component values are chosen from one domain (bounded), and

- there is a certain number of components present (finite).

To put this in fancy math symbols: Template:Center

Declaration

In Pascal we can declare file data types by specifying file of recordType, where recordType needs to be a valid record data type.

A permissible record data type can be any data type, except another file data type (including text) or a data type containing such.

That means an array of file data types, or a record having a file as a component is not permitted.

Let’s see an example:

program fileDemo(output);

type

integerFile = file of integer;

With a variable of the data type integerFile we can access a file containing only one kind of data, integer values (the domain restriction).

var

temperatures: integerFile;

i: integer;

Note, the variable temperatures is not a file by itself.

This Pascal variable merely provides us with an abstract “handle”, something that permits us, the program, to get a hold of the actual file (as described in § Concept).

Modes

All files have a current mode. Upon declaration of a file variable, this mode is, like usual, undefined. In Standard Pascal as defined by the Template:Abbr standard 7185 you can choose from either generation or inspection mode.

Generation mode

In order to write to a file you will need to call the standard built-in procedure named rewrite.

Rewrite will attempt opening a file for writing from the start.

begin

rewrite(temperatures);

The file immediately becomes empty, hence its name rewrite.

Extended Pascal also has the non-destructive procedure extend.

Only after successfully opening a file for writing, all write routines become legal. Attempting to write to a file that has not been opened for writing will constitute a fatal error.

write(temperatures, 70);

write(temperatures, 74);

All parameters to write after the destination (here temperatures) have to be of the destination file’s recordType.

There must be at least one.

Only if the destination is a text file, various built-in data types are permitted.

Note that the procedure(s) writeLn (and readLn) can only be applied to text files.

Other files do not “know” the notion of lines, therefore the …Ln procedures cannot be applied on them.

Inspection mode

In order to read a file you will need to call the standard built-in procedure named reset.

Reset will attempt opening a file for reading from the start.

reset(temperatures);

while not EOF(temperatures) do

begin

read(temperatures, i);

writeLn(i);

end;

end.

Note that after reset(temperatures) you cannot write anything to that file anymore.

Modes are exclusive:

Either you are writing or reading.[fn 1]

Application

The main and most apparent “advantage” of a file might be:

Unlike an array we do not need to specify a size in advance, in our source code.

The file can be as large as needed.

Yet an array can be copied with a := assignment.

Entire files cannot be copied this way.

The main “disadvantage” of a file might be:

Access is only sequentially.

We have to start reading and writing a file from the start.

If we want to have, say, the 94th record, we need to advance 93 times and also take account of the possibility that there might be less than 94 records available.[fn 2]

The words advantage and disadvantage were put between quotation marks, because a programming language cannot judge/rate what is “better” or “worse”. It is the programmer’s task to make the assessment. Files are especially suitable for Template:Abbr of unpredictable length, for instance user input.

Primitive routines

So far we have been using only read/readLn and write/writeLn.

These procedures are convenient and perfect for everday use.

However, Pascal also gives you the opportunity to have a comparatively “low-level” access to files, get and put.

Buffer

Every file variable is associated with a buffer.

A buffer is a temporary storage space.

Everything you read from and write to a file passes through this storage space before the actual read or write action is communicated to the Template:Abbr.[fn 3]

Buffered Template:Abbr is chosen for performance reasons.

In Pascal we can access one, the “current” component of the buffer by appending ↑ to the variable name, just as if it was a [[../Pointers|pointer]].

The data type of this dereferenced value is the recordType as in our declaration.

So if we have

var

foobar: file of Boolean;

the expression foobar↑ has the data type Boolean.

To put everything into relation to each other let’s take a look at a diagram. This diagram is about understanding and shows a very specific situation. Focus on the relationships:

The upper part is in the purview of the Template:Abbr.

The lower part is in the purview of the (our) program.

The data of the file, here a sequence of 16 integer values in total, are exclusively managed by the Template:Abbr.

Any access of the data is done via the Template:Abbr.

Directly reading or writing is not possible.

We ask the Template:Abbr to copy the first 4 integer data values for us into our buffer.

We do so, because copying 4 integers individually is slower than copying them all together in one go.[fn 4]

Sliding window

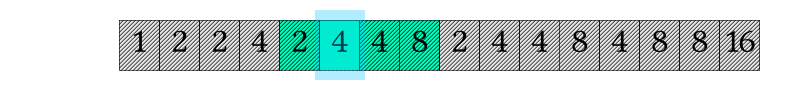

The three different storage locations – the actual data file, the internal buffer, and the buffer variable – work together in providing us a “view” of the file. If we overlay everything that contains the same information, we get the following image:

Here, the second quartet of integers was loaded into the internal buffer (green background). The file buffer points to the second component of the internal buffer. This is represented by a bluish hue over the sixth component of the entire file. Everything else is shaded, meaning we can view and manipulate only the sixth component.

Advancing the window

This sliding window can be advanced (in the rightwards direction, i. e. in the direction of Template:Abbr) with the routines get and put.

Both advance the file buffer to point to the next item in the internal buffer.

Once the internal buffer has been completely processed, the next batch of components is loaded or stored.

Calling get is only legal while a file is inspection mode; respectively put is only legal while a file is generation mode.

Using the window

Get and put take one non-optional parameter, a file (or text) variable.

Put takes the current contents of the buffer variable and ensures they are written to the actual file.

Let’s see this in action.

Consider the following program:

program getPutDemo(output);

type

realFile = file of real;

var

score: realFile;

begin

The following table shows in the right-hand column the state of score, the contents and where the sliding window is at (blue background).

| source code | state after successful operation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

rewrite(score);

|

| ||||||

score^ := 97.75;

|

| ||||||

put(score);

|

| ||||||

score^ := 98.38;

|

| ||||||

put(score);

|

| ||||||

score^ := 100.00

|

| ||||||

{ For demonstration purposes: no `put(score)` here. }

|

|

Now let’s print the file score we just filled with some real values.

For a change we use get.

Like read/readLn, getis only allowed if not EOF:

reset(score);

while not EOF(score) do

begin

writeLn(score^);

get(score);

end;

end.

Note that this prints just two real values:

9.775000000000000E+01

9.838000000000000E+01

The third real value, although defined, was not written by a corresponding put(score)

Requirements

As mentioned above, get may only be called when the specified file is inspection mode, whereas put may only be called when the file is generation mode.

More specifically, calling get(F) is only allowed when EOF(F) is false, and calling put(F) is only allowed when EOF(F) is true.

In other words, reading past the Template:Abbr is forbidden, while writing has to occur at the Template:Abbr.

After successfully calling rewrite(F) (or the Template:Abbr procedure extend(F)) the value of EOF(F) becomes true.

Any subsequent put(F) does not alter this value.

After calling reset(F) the value of EOF(F) depends on whether the given file is empty.

Any subsequent get(F) may change this value from false to true (never in the reverse direction).

Text buffer

The buffer value of a text has some special behavior.

A text file is essentially a file of char.

Everything presented in this chapter can be applied to a text file just as if it was file of char.

However, as repeatedly emphasized, a text file is structured into lines, each line consisting of a (possibly empty) sequence of char values.

When EOLn(input) becomes true, the buffer variable input↑ returns a space character (' ').

Thus when using buffer variables the only way to distinguish between a space character as part of a line, and a space character terminating a line is to call the function EOLn.

Template:Wikipedia Rationale: Various operating systems employ different methods of marking the end of a line. It has to be marked somehow, because this information cannot be magically deduced out of nowhere. However, there are multiple strategies out there. This is really inconvenient for the programmer who cannot take account of everything. Pascal has therefore chosen that, regardless of the specific Template:Abbr marker used, the buffer variable contains a simple space character at the end of a line. This is predictable, and predictable behavior is good.

Purpose

It is worth noting that all functionality of read/readLn and write/writeLn can at their heart be based on get and put respectively.

Here are some basic relationships:

If f refers to a file of recordType variable and x is a recordType variable, read(f, x) is equivalent to

x := f^;

get(f);Similarly, write(f, x) is equivalent to

f^ := x;

put(f);For text variables the relationships are not as straightforward.

The behavior depends on the various destination/source variables’ data types.

Nonetheless, one simple relationship is, if f refers to a text variable, readLn(f) is equivalent to

while not EOLn(f) do

begin

get(f);

end;

get(f);The latter get(f) actually “consumes” the newline marker.

Support

Unfortunately, from the compilers presented in the [[../Getting started#Required software|opening chapter]], Delphi and the Template:Abbr do not support all Template:Abbr 7185 functionality.

- Delphi and the Template:Abbr require files to be explicitly associated with file names before performing any operations. It is required to back any kind of

fileby a file in background memory (e. g. on disk). How this works will be explained in the second part of this book, since Template:Abbr standard 10206 “Extended Pascal” defines some means for that, too. - The Template:Abbr provides the procedures

getandput, and file variable buffers only in{$mode ISO}or{$mode extendedPascal}. Delphi does not support this at all.

Rest assured, everything works fine if you are using the Template:Abbr. The authors cannot make a statement regarding the Pascal‑P compiler since they have not tested it.

Tasks

Template:Question-answer Template:- Template:Question-answer Template:- Template:Question-answer Template:Newpage

Template:Auto navigation

Cite error: <ref> tags exist for a group named "fn", but no corresponding <references group="fn"/> tag was found