Control Systems/Bode Plots

Bode Plots

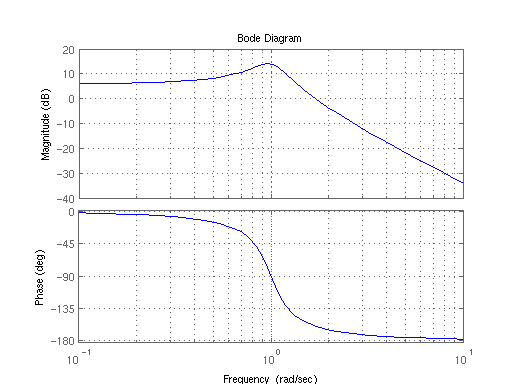

A Bode Plot is a useful tool that shows the gain and phase response of a given LTI system for different frequencies. Bode Plots are generally used with the Fourier Transform of a given system.

The frequency of the bode plots are plotted against a logarithmic frequency axis. Every tickmark on the frequency axis represents a power of 10 times the previous value. For instance, on a standard Bode plot, the values of the markers go from (0.1, 1, 10, 100, 1000, ...) Because each tickmark is a power of 10, they are referred to as a decade. Notice that the "length" of a decade decreases as you move to the right on the graph. (note that this description doesn't match the chart above... there are 10 tickmarks per decade, not one, but since it is a log chart they are not evenly spaced).

The bode Magnitude plot measures the system Input/Output ratio in special units called decibels. The Bode phase plot measures the phase shift in degrees (typically, but radians are also used).

Decibels

A Decibel is a ratio between two numbers on a logarithmic scale. To express a ratio between two numbers (A and B) as a decibel we apply the following formula for numbers that represent amplitudes (numbers that represent a power measurement use a factor of 10 rather than 20):

Where dB is the decibel result.

Or, if we just want to take the decibels of a single number C, we could just as easily write:

Frequency Response Notations

If we have a system transfer function T(s), we can separate it into a numerator polynomial N(s) and a denominator polynomial D(s). We can write this as follows:

To get the magnitude gain plot, we must first transit the transfer function into the frequency response by using the change of variables:

From here, we can say that our frequency response is a composite of two parts, a real part R and an imaginary part X:

We will use these forms below.

Straight-Line Approximations

The Bode magnitude and phase plots can be quickly and easily approximated by using a series of straight lines. These approximate graphs can be generated by following a few short, simple rules (listed below). Once the straight-line graph is determined, the actual Bode plot is a smooth curve that follows the straight lines, and travels through the breakpoints.

Break Points

If the frequency response is in pole-zero form:

We say that the values for all zn and pm are called break points of the Bode plot. These are the values where the Bode plots experience the largest change in direction.

Break points are sometimes also called "break frequencies", "cutoff points", or "corner points".

Bode Gain Plots

Bode Gain Plots, or Bode Magnitude Plots display the ratio of the system gain at each input frequency.

Bode Gain Calculations

The magnitude of the transfer function T is defined as:

However, it is frequently difficult to transition a function that is in "numerator/denominator" form to "real+imaginary" form. Luckily, our decibel calculation comes in handy. Let's say we have a frequency response defined as a fraction with numerator and denominator polynomials defined as:

If we convert both sides to decibels, the logarithms from the decibel calculations convert multiplication of the arguments into additions, and the divisions into subtractions:

And calculating out the gain of each term and adding them together will give the gain of the system at that frequency.

Bode Gain Approximations

The slope of a straight line on a Bode magnitude plot is measured in units of dB/Decade, because the units on the vertical axis are dB, and the units on the horizontal axis are decades.

The value ω = 0 is infinitely far to the left of the bode plot (because a logarithmic scale never reaches zero), so finding the value of the gain at ω = 0 essentially sets that value to be the gain for the Bode plot from all the way on the left of the graph up till the first break point. The value of the slope of the line at ω = 0 is 0 dB/Decade.

From each pole break point, the slope of the line decreases by 20 dB/Decade. The line is straight until it reaches the next break point. From each zero break point the slope of the line increases by 20 dB/Decade. Double, triple, or higher amounts of repeat poles and zeros affect the gain by multiplicative amounts. Here are some examples:

- 2 poles: -40 dB/Decade

- 10 poles: -200 dB/Decade

- 5 zeros: +100 dB/Decade

Bode Phase Plots

Bode phase plots are plots of the phase shift to an input waveform dependent on the frequency characteristics of the system input. Again, the Laplace transform does not account for the phase shift characteristics of the system, but the Fourier Transform can. The phase of a complex function, in "real+imaginary" form is given as:

Bode Procedure

Given a frequency response in pole-zero form:

Where A is a non-zero constant (can be negative or positive).

Here are the steps involved in sketching the approximate Bode magnitude plots:

Here are the steps to drawing the Bode phase plots: